The new HELP repayment system legislated this week will move from HELP debtors repaying a % of total income to a % of income above the repayment threshold, a marginal system. In introducing the bill to Parliament, education minister Jason Clare quoted Bruce Chapman on a marginal system: 'it's much gentler and much fairer than previously—we should have done it years ago.'

While the new marginal repayment system may be gentler and fairer, it could create more widespread disincentives to working additional hours than the current total income system.

The problem with total income systems

The Universities Accord Final Report, which guides the government’s higher education agenda, criticised the total income repayment as unfair and a deterrent to work.

The underlying problem is that a multi-rate total income repayment system creates multiple threshold ‘cliffs’, income points at which earning $1 more triggers a big increase in student debt repayment. The most extreme cliffs are the lower income levels. Under the current system a debtor whose income reaches the $56,156 first threshold faces an increase in repayments from $0 to $561.56, plus 30 cents of income tax. By earning more the student debtor reduces their take-home pay. Repayment cliffs exist, at less extreme levels, at all 18 income thresholds in the current student debt repayment system.

A total income repayment system produces some very high effective marginal tax rates (EMTR). An EMTR is jargon for how much of an extra dollar earned is lost to income tax, withdrawal of benefits, and in this case HELP repayments. EMTRs are a big issue in Australia’s welfare state, which makes widespread use of means tests – of which the HELP repayment thresholds are a version.

Do high HELP EMTRs matter?

There is evidence that HELP EMTRs affect debtor behaviour. To avoid losing take-home pay, some debtors manipulate their HELP repayment income, which is taxable income with a few variations – such as by working fewer hours or claiming tax deductions – to reduce student debt repayments. The Accord Final Report produced evidence of ‘bunching’ of HELP debtor income, with higher-than-expected numbers of debtors reporting incomes just below the first threshold.

Other researchers have also identified bunching around HELP repayment thresholds. Tim de Silva’s work on the current system finds, unsurprisingly, that apparent income manipulation is more common in occupations with flexible and variable hours, such as hospitality and sales work. Full-time workers cannot manipulate employment income as easily as part-time or casual staff. Beyond lost or delayed HELP repayment revenue, suppressing income also reduces income tax revenue, creating additional costs for government. If the labour market is tight, reduced work hours by HELP debtors could have further negative economic consequences.

While high HELP EMTRs are indisputably an issue, they are not completely analogous with the loss of means-tested benefit payments such as - to use an education example - Austudy. With Austudy, payments lost due to the income test are lost forever. With HELP repayments the person’s student debt is reduced. Repayments now will reduce future debt indexation and repayments – at least for people who clear their debt.

But will the new repayment system reduce disincentives to working more hours?

The marginal repayment system will definitely get rid of all HELP EMTRs between $56,156 and $67,000, due to the new higher first repayment threshold. It will definitely get rid of the crazy-high HELP EMTRs just above repayment thresholds.

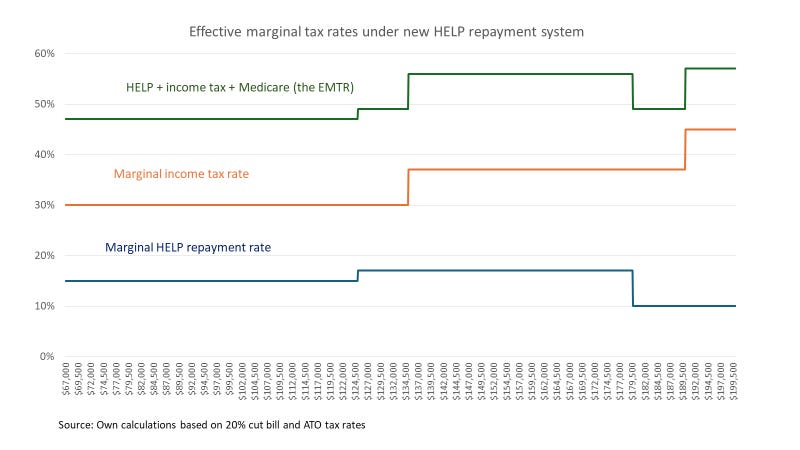

But once the $67,000 threshold is crossed I am not sure that the new system will improve work incentives compared to the old one. As can be seen in the chart below, everyone in the HELP repayment system will have an EMTR of at least 47% - equivalent to the top marginal tax rate for high income earners + Medicare. Many other income levels have higher EMTRs than this (the strange downward kink in HELP repayments for high income earners is due to capping repayments at 10% of income, but they quickly lose the HELP EMTR benefit to the 45% tax bracket; it is messy but few HELP debtors have incomes in these ranges).

For EMTRs to drive HELP debtor behaviour the debtor needs to know what they are. Under the current system, EMTRs are confusing - calculating them requires a spreadsheet and they change constantly as income goes up through 18 thresholds. I doubt many people use a % rate in decision-making, but clearly some people understand and act on the negative cash flow consequences of moving across a threshold.

But if crossing a threshold under the current system is seen as a sunk cost/repayment then the marginal repayment cost of earning another dollar is low - somewhere between the current minimum 1% and maximum 10% of total income, depending on personal earnings.

Under the new system the HELP EMTRs are much simpler for most people - 15% or 17%. It is therefore much easier to take HELP repayment rates into account when deciding whether to work extra hours or not. And 15% and 17% sound much higher than the current rates if you don't understand the difference between total and marginal income repayment systems.

Conclusion

In the choice between the current and new repayment systems there was a trade-off: between a small number of well-informed people having a large cash incentive to change their income-earning behaviour and a large number of people having a smaller but more noticeable disincentive to working more hours.

Perhaps these things don't matter hugely. The new $67,000 threshold will completely knock many flexible-hours workers out of the repayment system. Once graduates are in their careers, and no longer doing casual work with flexible hours, they will take additional income even if they won't see as much of it as they would like - as happens under the current system.

Elevated EMTRs are the price paid for an income-contingent rather than a mortgage-style fixed regular repayment system of recovering student debt. Overall this is a price worth paying.

But I am not convinced that, at a total debtor population level, the EMTR problem under the new system will be smaller than under the current system - even if is gentler and fairer for the people currently facing reduced take-home pay despite increased income.