For a side-project I've recently engaged with the subject of whether higher education funding systems shape the educational and career choices of students and graduates.

On one theory, where fees are charged students focus more on courses and jobs with high pay. Courses that satisfy intrinsic interests but do not offer good salary prospects would be less popular in countries with fees or after fee increases. Focus-group research on the views of students in European countries provides some support for this view (I have not cross-checked this against enrolments).

Under fee systems, depending on loan arrangements, taking courses with good job prospects may be necessary to reduce the risk of default on student debt repayments.

On another theory, also with some evidence from the European focus-group research, students in fee-paying countries may be more interested in courses that lead to personal financial rewards than courses that serve some broader public purpose. There are echoes of this argument in the local complaint that Australian higher education in the 'neoliberal' fee-charging era has lost sight of the 'public good'.

I've discussed the role of interests in course choices before. In this post I look at the attitudes of graduates. My data source is survey evidence from the International Social Survey Programme. Unfortunately Australia only occasionally participates in these multi-nation comparative studies, but the ISSP's 2015 work orientation questionnaire has Australian data.

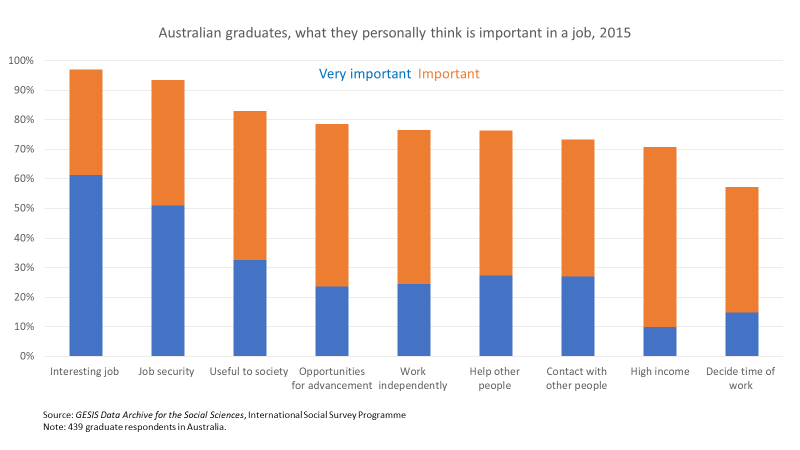

What Australian graduates see as important in a job

In the ISSP respondents are asked what job attributes they personally see as important.

A job being interesting is the single-most desirable attribute of a job for Australian graduates. This is consistent with interests being the dominant factor in course choice.

The ISSP question has two other-regarding options, being useful to society and helping other people. I presume helping others is a hands-on form of being useful, such as a teacher or nurse, while a policymaker, engineer or executive can produce useful-to-society structures and systems without directly helping specific individuals.

Perhaps because being useful to society is more general it is rated above helping others, and is the third mostly highly rated attribute overall.

Only 10% of graduates rate a high income as very important, the lowest of any attribute and the overall importance of money is the second-lowest of the options given. Money is nice to have but other job attributes are more important.

Australian graduates in comparative perspective

For my international comparisons I chose three groups of countries. Three countries are in Asia - Taiwan, China and Japan - with all charging fees without income-contingent loans. Three countries - the United States, Australia and Great Britain - are English speaking and all charge fees. Only the US has done so continuously in the lifetimes of people who may have responded to the ISSP survey, but by 2015 most Australian graduates would have paid for their higher education. Australia and England have income-contingent loans, the US has a messy patchwork of funding mechanisms. Germany, France and Sweden are continental European welfare states where higher education is free or very cheap.

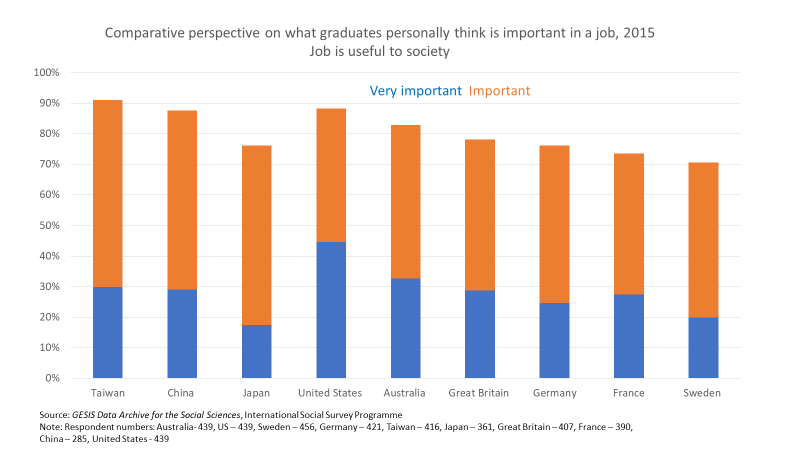

Importance of jobs being useful to society

In all nine countries the vast majority of graduates believe a job being useful to society is important.

The high results for Taiwan and China are consistent with these being relatively collectivist cultures, where we might expect social obligations to be more prominent than in relatively individualistic and culturally European countries. That theory, however, does not explain why the Japanese result looks European.

Among the more individualistic countries it is the US, with the most consistent history of charging fees, that has the largest share of graduates who see a job being useful to society as important. The US higher education system is a case study in the intellectual risks of conflating funding sources and the purposes of institutions or students. Universities in the US have traditions of promoting civics, including in their admissions systems.

The share of graduates rating being useful to society as important is lower than elsewhere in the free/very cheap education European countries and lowest in Sweden. While I would not draw too much from this - across the nine countries the similarities are more striking than the differences - it is contrary to hypotheses about the relationship between fees and motivations. Perhaps there is something to the idea that, in countries with larger welfare states, more people assume that the government should help others, and that as a result obligations on individuals are weaker.

Australia ranks fourth of the nine countries on this metric, though for the share rating a job being useful to society as 'very important' it is second after the US.

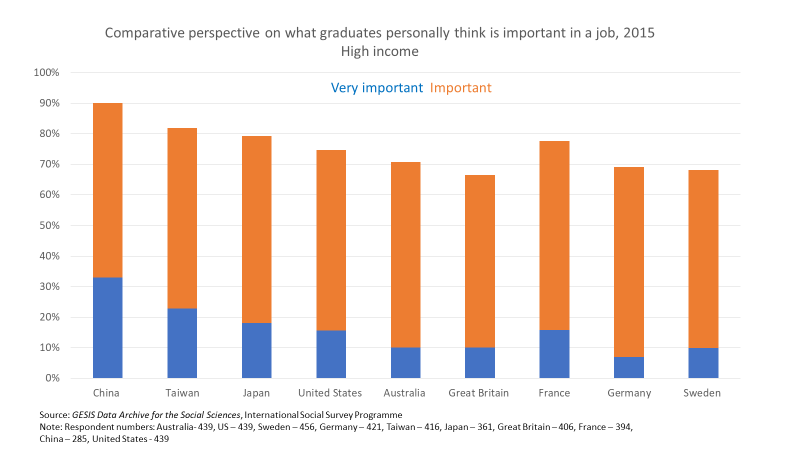

Importance of high income

When we compare countries on the importance of high income as a job attribute then Taiwan and China are perhaps a case study in Adam Smith's seemingly paradoxical idea that pursuing one's own interests is not inconsistent with serving the interests of others. Graduates in these countries rate high incomes for themselves and being useful to society highly. Possibly the emphasis on income is explained by post-materialist theory, which argues that as countries get richer priorities shift towards non-material goals. China and to a lesser extent Taiwan are 'new money' countries in which low living standards are too fresh in cultural memory for post-materialist goals to have the influence they do in many Western countries.

The graduates with the least interest in money are, in order, Great Britain, Sweden, Germany and Australia - a pattern not clearly explained by higher education financing practices. However, except for France the free/very cheap countries put a relatively low emphasis on jobs having high incomes.

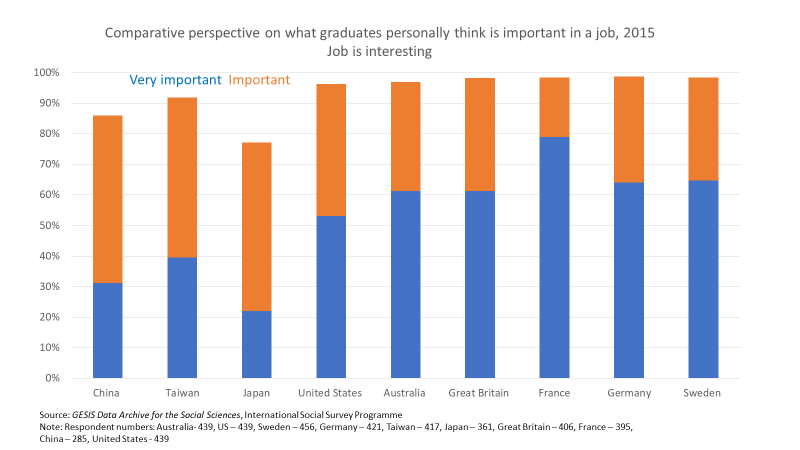

Importance of a job being interesting

In every country the vast majority of graduates rate a job being interesting as important.

However the three Asian countries in my comparison, and especially Japan, have noticeably lower shares of graduates rating a job being interesting as important - perhaps a trade-off with high income and/or being useful to society.

In the aggregates, the culturally European countries are very similar although in France the proportion of graduates rating how interesting a job is as 'very important' is unusually high.

Conclusion

Despite the partial exceptions in Asia, the 2015 ISSP results are consistent with interests being the dominant driver of course and career choices.

As with outcome measures like participation and attainment rates, job motivations and priorities have parallels across countries regardless of how higher education is funded.

The Japanese outlier

The Japanese results look unusual. Perhaps there is an issue with the sample, but then again Japan is popular partly because it does seem strange to Westerners.

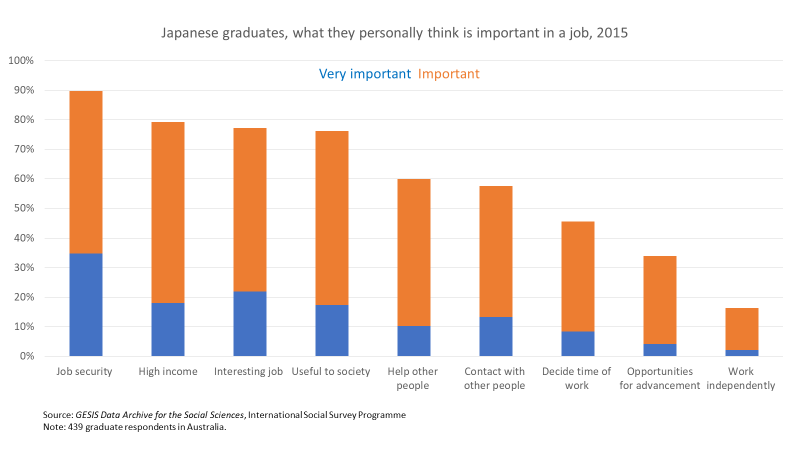

Here are the Japanese results for all the job criteria questions:

Perhaps with the idea of lifetime employment with a single firm having currency in Japan, in a way that it typically does not elsewhere, it is not too surprising that 'job security' is the highest-rated job criterion. Japanese graduates report low preferences for deciding their time of work, having opportunities for advancement and working independently - factors Australians graduates see as desirable in a job (ranging from 57% to 78% important) but in Japan are much less important than job security.