The new HELP repayment system and lifetimes of student debt

The prime minister says that a degree should not come with a lifetime of debt. For that goal, the government's HELP legislation introduced last week is contradictory. It will cut all debt owed as of 1 June 2025 by 20%, which will shorten repayment times for current debtors. But it will also cut annual debt repayments for 99% of debtors, which will lengthen compulsory repayment times for many and push others into the PM's lifetime of debt.

In the analysis below, female debtors owing $25,000 or more with incomes in the lowest 40% of graduate earnings face an increased risk of a lifetime of student debt. However, what percentage of female debtors actually face a lifetime of debt will depend on initial debt levels and how much their incomes vary through their careers. Voluntary repayments can also affect repayment times.

How the repayment system will change

My previous post on the initial threshold summarised how the repayment system will change. The key elements are that 1) repayment exempt incomes will include everyone on $67,000 or less compared to less than $56,156 now and 2) a marginal rather than total income repayment system will reduce what most debtors repay, particularly at lower income levels.

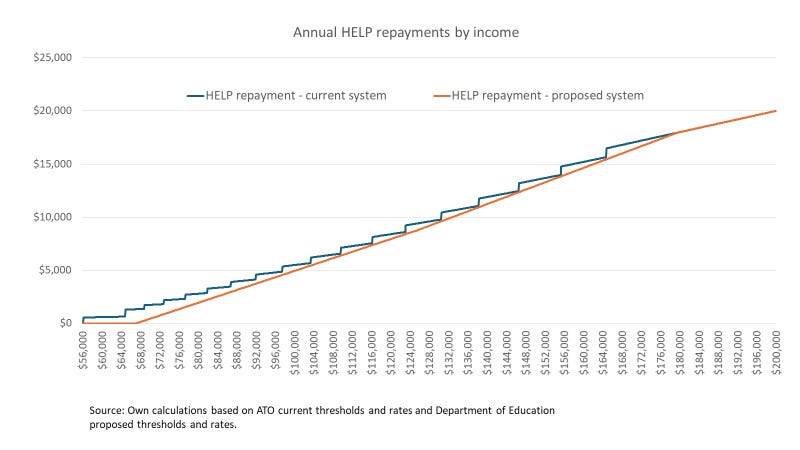

The chart below shows how this will affect HELP debtors at different annual income levels. Based on 2022-23 ATO data I estimate that 99% of debtors repaying under current thresholds will repay less per year than under the current system. The other 1%, all high income earners, will repay the same amount per year as now.

Debt treadmill

The combination of an increased initial repayment threshold and the marginal repayment system risks putting more debtors than now on a debt treadmill, repaying nothing each year or less than the amount of their indexation.

This is most dangerous to a HELP debtor's long-term finances in early career, when their underlying borrowing is at its peak. If they don't make any significant repayments their indexation will compound, making it harder to get control of their debt. They risk the PM's lifetime of debt.

A caveat to my analysis

The government, which has access to the real repayment history of all current and former debtors, has not produced any analysis of the likely repayment trajectories. The PBO has done some work on this. In an attempt to provide additional guidance I will use 2021 Census income data derived from the ATO and DSS, which is for the 2020-21 tax year. I have increased it by the wage price index to make income levels more comparable to today's thresholds.

The most important caveat to my analysis is that it assumes that if someone is, say, on the median graduate income at age 21 they will remain at the median for their whole career. Clearly there will be variance from fixed relative positions in most cases. A matter that is especially important for this analysis is movements in and out of the labour force and between part- and full-time work. Especially for women movements in and out of full-time work have a big impact on repayment prospects that I cannot properly account for using the data sources I have.

Two stress test debt levels

In my analysis I chose two HELP balance stress tests. In the first graduates commence their careers at age 21 with $40,000 in HELP debt. In the second the debt level is $25,000. In each case I assume indexation of 2.5% a year.

I give a repayment system a pass grade if full repayment occurs within 20 years.

Median income

For graduates on the median income I will not show the detailed repayment trajectories because both men and women pass most of my stress tests on both the current and proposed repayment systems. Under the proposed system women's repayment times fall just short of the time test with a $40,000 debt.

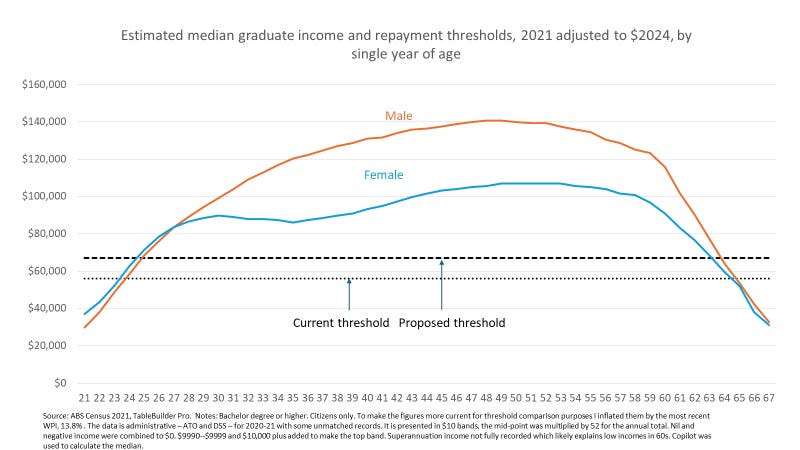

You can see on the chart below that there are some below-threshold incomes in early career, which causes debt to go up before it goes down. Once past this point, however, incomes are consistently comfortably above the initial repayment thresholds.

Men should clear a $25,000 debt by age 32 under the current system and age 33 under the proposed system. They should clear a $40,000 debt by age 35 under the current system and age 36 under the proposed system. The estimates are similar for each system because, as can be seen in the first chart, once incomes reach the higher levels annual repayments are significant for both systems. In the late part of the repayment phase the median income male repays $6000+ a year, which cuts the balance quickly.

For women repayment times are slower. While women earn more than men up to age 27, from there they fall behind.

With a $25K debt under the current repayment system the debt for women on the median graduate income will be cleared by age 33, one year more than for men. With the proposed system a $25K debt will be cleared by age 36, three years more than men, but with only $214 remaining in the last year - so just a quirk of how the calculations happened to fall. Slight variations in income, indexation etc would bring the years back down again.

A $40K debt would be gone by age 39 under the current system and 43 under the new system, just above my 20-year repayment mark.

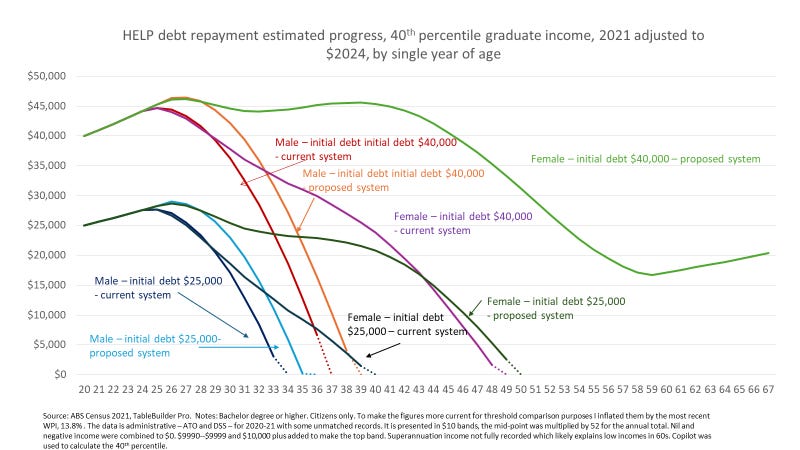

Income at the 40th percentile

At the 40th percentile there are more problems for female debtors, especially with a $40K initial debt. On these calculations they will make progress in debt repayment under the proposed system but nevertheless have the prime minister's lifetime of debt under the proposed system. Under the current system a female debtor will clear the original $40K by age 49.

At a $25K debt level the current system sees repayment finish at age 40, a pass, and the proposed system at 50, so a long period of debt but not a lifetime.

For males the proposed system has longer repayment times but both systems get a pass, with estimated repayment ages at under 40 in all cases.

Income at the 30th percentile

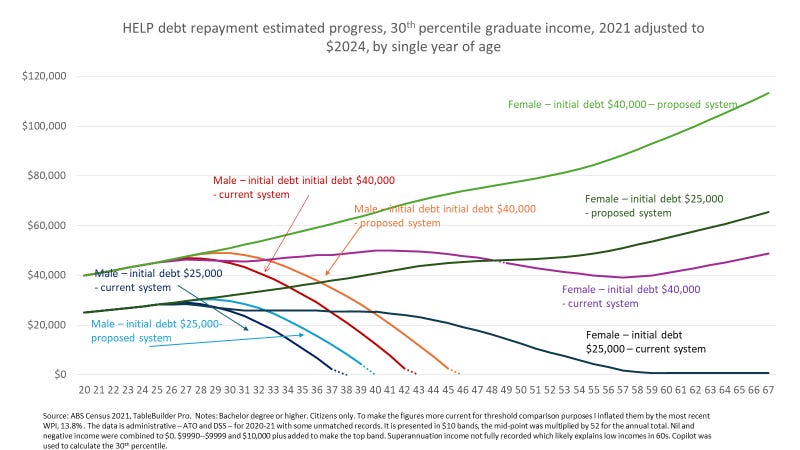

At the 30th income percentile female debtors are looking at lifetimes of debt, although under the current repayment system a $25K debt gets down to $700 at its low point, so minor variations in the many assumptions made in this analysis could see it wiped completely.

The core problem with the proposed system at the 30th percentile is that although repayments are made in 17 years they are all below $1000. As a result the debtor ends up owing more in retirement than they did when they left university. Cutting debt by 20% may deliver some psychological benefit to this group but will not make any difference to their annual repayments or full repayment prospects.

Again the men have longer repayment times under the proposed system but do clear their debts.

Further analysis

As noted, a key weakness of this analysis is variations in labour force participation, especially for women. I aim to look into this in a subsequent post.