The Coalition's plan to reduce international student numbers - first thoughts

As rumoured in recent months, the Coalition has decided, if it wins office on 3 May, to cap commencing international student enrolments at a percentage of all commencing enrolments. The precise number is yet to be settled, but is expected to be around 25% and will only apply to public universities.

Student experience as well as migration concerns

A key conceptual difference with the government's policy is that the Coalition wants to improve the domestic student experience as well as take pressure off accommodation markets. That's why they chose a % of enrolments rather than, as under Labor, formulas driven by past enrolment patterns - although Labor did include a penalty for institutions with high concentrations of international students.

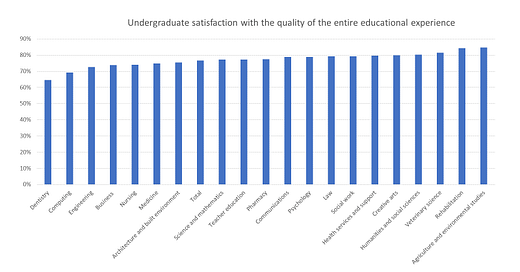

So far as I know, no careful research examines whether high concentrations of international students adversely affect domestic students in measurable ways. There are many anecdotal complaints, especially around group assignments. Is it a coincidence that computing, engineering and business courses, which have high concentrations of international students, have relatively low student satisfaction (chart below)?

Perhaps international students have nothing to do with it. Long ago, looking at the old CEQ results, I observed that students in vocational courses seem less satisfied than other students. Speculatively they have more instrumental motivations, and so enjoy study less. They study in fields where universities compete with industry and the professions for staff. Academic salaries might not attract the best possible teachers.

Questions about the domestic student experience are at least worth asking and answering as best we can. Universities are too conflicted to do it or release the results if they do. It's another argument for making higher education data available to researchers inside and outside the academy (e61 is doing a great job on this kind of research).

A proportion of a variable number

In itself, a fixed proportion of enrolments would provide an easier-to-explain and more transparent international student capping formula than Labor's 2024 proposal.

But the denominator of total enrolments moves constantly as students enrol and finish or drop out during the year.

From a policy implementation perspective, the government is either unable or unwilling to provide up-to-date enrolment figures that include domestic students. TCSI was supposed to fix this problem but instead it seems to have made things worse.

Perhaps the base number could be domestic students in the year preceding the regulated year, but even that figure cannot be produced with 100% accuracy on timelines that match the recruitment period for international students.

Non-public university providers

The 25% limit would not apply to private higher education and vocational education providers. It would not make sense for some of them, since international students are their main market.

The Coalition's media release say there would be a total cap of 125,000 for these providers. That's about 7,000 less than under Labor.

From the questions and statements of Coalition senators during the various inquiries into Labor's bill there would be a more nuanced examination of provider circumstances.

Regardless of who is in power I expect a cleaning out of the more dubious vocational education providers.

With weak demand for vocational education visas it should also be the case that some providers have within-cap places they cannot use. These can be redistributed to providers that have demand exceeding their cap (or a cap-and-trade system could be established).

Definition of commencing enrolments

I presume that offshore students are excluded from both the international student and the total commencing enrolment counts. That is not expressly stated in the Coalition media release, but offshore students are irrelevant to migration and domestic student experience concerns.

A trickier issue is the count of commencing students. Labor's ministerial direction 111 only applies to offshore applicants, but to achieve the policy goals onshore applicants also need to be counted. That would raise further issues about whether to count the backlog of unprocessed onshore visa applications and the visa refusal appeals waiting to be heard by the Administrative Review Tribunal.

Labor has exceptions to its capping policy. Two of these, schools and standalone ELICOS courses, are also impliedly excluded from capping by the Coalition's media release, which mentions only vocational and higher education providers.

Other Labor exceptions - students from the Pacific and Timor-Leste, research students, students with government scholarships, students enrolled in some transnational education programs, and non-award students - are not mentioned in the Coalition policy. Some recent estimates put these at 8% of higher education students and 4% of vocational students.

Labor's policy is also to count students new to the education provider rather than new to the course. If the Coalition counted new to the course that would be more restrictive.

Synching domestic and international enrolment cycles

A couple of times this century universities have benefited from domestic and international markets working on different drivers.

An early 2010s decline in international students was offset by the demand driven domestic student boom.

More recently a bad year for domestic enrolments in 2023 was offset by a booming international student market.

If international students were capped at a fixed proportion of total enrolments fewer domestic students would also mean fewer international students.

Regulatory mechanisms - funding agreements

On Sunday a journalist asked Peter Dutton if universities would evade the cap by enrolling more domestic students. Dutton replied that:

"Firstly, we have looked very closely at the way in which the agreements work between the government and the universities. We can put requirements in because the Commonwealth obviously is the funder of the universities. So, we will meet our policy objectives through those arrangements."

Presumably this is a reference to the Commonwealth Grant Scheme funding agreements. At least in broad terms, by limiting CGS payments, the funding agreements can constrain domestic Commonwealth-supported student numbers with minimal legal controversy.

But can the funding agreements be used to limit international student numbers as well? Regular readers may recall my past objections to using the funding agreements to either undermine the intent of the legislation or to achieve policy goals that should be dealt with elsewhere, such as the regulation of early offers. But section 30-25(2) of the Higher Education Support Act 2003, which authorises additional conditions that can be added to funding agreements other than those expressly mentioned, is potentially a basis for regulating international student numbers.

So far the universities have always just accepted any funding agreement condition. If they don't sign they don't get their CGS money. But a cap on international student numbers might be big enough for them to at last take the Commonwealth to court, to see if section 30-25(2) is a 'the government can do whatever it wants' clause or whether it should be read more narrowly, as restricted to matters closely related to the use of Commonwealth supported places.

On the other hand, universities might see a funding agreement approach as preferable to migration-based regulation. They could manage their student numbers through the year to ensure that they don't exceed their 25% international share, rather than targeting a number that, for the reasons discussed above, would have to be based on old or estimated data. If domestic or international numbers vary from expectations there is time during the year to rebalance them.

Regulation could be retrospective with fines for universities that get their sums wrong (or technically a reduction in a grant, the legal penalty for breaching a funding agreement condition).

One concern universities would have about funding agreements is that in recent times they have been changed at least annually and often more regularly (it is only April but the 2025 funding agreements are already in their second iteration). They also tend to be signed very late in the prior year - the first 2025 funding agreements were signed on 20 December 2024. That's too late to manage international student offers for the next academic year. A legislated 25% cap would avoid this problem.

While the funding agreements are a potential regulatory device for public universities, most higher education providers don't have them because they don't receive any CGS funding. About 60 of them are totally outside the public higher education finance system - their students don't get HELP loans.

Regulatory mechanisms - migration policy

The Coalition's media release says they will manage the caps of private education providers 'through the migration system'.

I'm not expert enough on migration law to say whether there are existing options to achieve this goal. On my novice reading of the migration legislation last year the immigration minister has the power to cap a visa category, such as student visas. There is power to issue instructions on the order in which visa applications are considered (as happened for ministerial direction 107 and is happening for ministerial direction 111). But there is no existing power to set formal sub-quotas for different categories of provider.

So while the order of processing can influence who gets a visa, an annual cap favours applicants who can get their visa applications in early, and so maximise their chance of being accepted before the total cap is hit. That is not a precise enough mechanism. It would also add another layer of unpredictability, as neither students nor providers would have high visibility on where processing is at relative to the cap. If we are going to charge visa applicants high fees - and the Coalition would increase them again - we need to offer them something better than a lottery system.

I stand to be corrected on migration law, but if existing provisions could be used to target private education providers I am surprised that they have not been used already. Presumably Labor went down the ESOS Act route in the first place because they lacked legal authority to impose detailed caps, and then went down the ministerial direction 111 path as a second-best option for the same reason.

It seems likely, therefore, that an effective cap on private education providers will need legislation.

If a Coalition government tried to legislate its changes it is possible that either the Senate or (in the event of a minority Liberal government) the House of Representatives Opposition plus crossbench would block it.

The politics of this issue are far from over.