Temporary graduate visas - trends in applications, grants and populations

As part of its international student policy announcement, the Coalition promised a 'rapid review into the Temporary Graduate Visas (subclass 485)'. The review would 'address the misuse of post-study work arrangements as a way to gain access to the Australian labour market and as a pathway to permanent migration.'

While recent polls suggest the Coalition will not form government, net overseas migration will remain an important political issue. It is worth understanding trends in major migration categories such as the 485 visa.

This post summarises the available 485 visa data. A key point is that although applications for new 485 visas in 2024-25 to date are lower than in previous years, in the coming years there is the potential for significant increases in total 485 visa holder numbers.

Purpose of the 485 temporary graduate visa

Today's temporary graduate visa is descended from an early 2010s policy that was designed to make Australia more competitive in the international education market. It does this by letting former international students access the labour market, so doing this is not 'misuse' according to the policy's intent. The pathway element is more contentious. The 485 visa can be a pathway to permanent residence but it offers no guarantees. Government and student expectations proably differ on this matter.

In any case, as the numbers reported below show, there is no way all 485 visa holders in Australia in early 2025 could transition to a permanent migration program of 185,000 people for 2024-25.

Trends in the number of temporary graduate visa holders

The Department of Home Affairs does not publish how many people hold a 485 visa. The closest we get to a stock figure is a monthly count of temporary migrants in Australia. As at 28 February 2025, 214,714 people were in Australia on 485 visas. This was about 14,000 down on the 30 September 2024 peak. The monthly in-country totals undercount visa holders as some are temporarily overseas.

Since 2022 the primary visa holder share of the total - that is, the former student with the relevant qualification - has decreased from 75-80% of the total to 70-72%. There has been greater growth in secondary visa holders, the partners and children of primary visa holders.

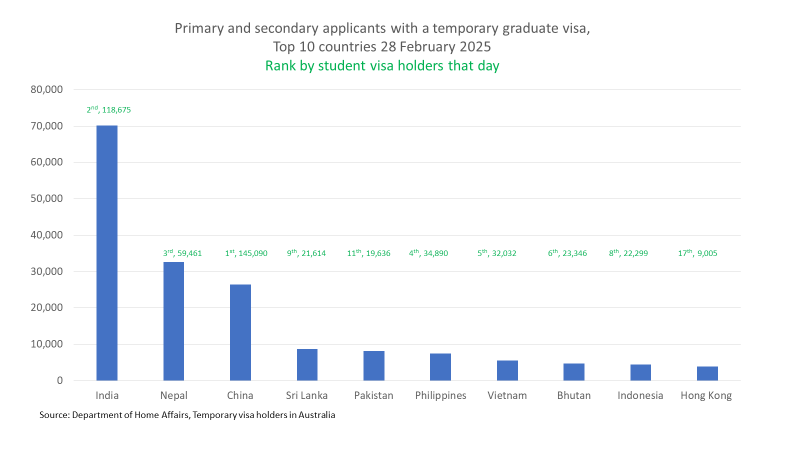

Country of origin of 485 visa holders

The numbers of 485 visa holders relative to the number of students by country reflects different migration priorities. China is the biggest source country for students but ranks 3rd for 485 visa holders. India is the second largest source of students but has by far the highest number of 485 visa holders. Between them, people from countries in South Asia made up 60% of 485 visa holders but 37% of students on 28 February 2025.

Hong Kong ranks 10th in 485 visa holders by home location but 17th for students. Hong Kong passport holders are eligible for a five year 485 visa compared to 18 months to three years for most source countries. For the same political reason, graduates from Hong Kong may be more likely to apply for a 485 visa than graduates from other high-income Asian locations.

485 visa holders by education background

There are two broad types of 485 visa. What is now called the post-vocational education work stream (previously the graduate work stream) is the more difficult to get. It is for people with a diploma or trade qualification closely related to occupations deemed to be in demand for migration purposes. The vocational 485 visa lasts for 18 months.

What is now called the post-higher education work stream (previously the post-study work stream) is for people with a bachelor degree or above. For this visa, the are no occupational restrictions (although for 2023-24 applicants could get an extra two years for degrees in some fields). The higher education 485 visa lasts for at least 2 years. The length of masters and above 485 visas was reduced from 1 July 2024. This post has more on visa lengths and how they changed.

We can see that the vocational stream spiked up after COVID but in more recent months has trended down, both for reasons explained below. Higher education showed more volatility but has increased its share of 485 visa holders.

485 visa grants

In 2022-23 the number of 485 visas issued was much larger than in previous or subsequent financial years.

One reason was that the incoming Albanese government made a big effort to work through a backlog of more than 60,000 unprocessed 485 visa applications. Monthly data shows that the biggest 485 visa grant months for the January 2019 to February 2025 period were, in order of size, August 2022, December 2022, and October 2022.

Demand for vocational 485 visas went up for temporary reasons. The Morrison government decided to suspend the requirement to nominate an occupation from the skill shortage list and extend the visa length from 18 months to 24 months. The progressive expiry of these easier-to-get vocational visas and fewer visa grants in subsequent years presumably explains why the vocational stream numbers are trending down.

For higher education temporary graduate visa applicants the Morrison government extended the length of a masters 485 from two to three years in late 2021. As these students were already eligible the effect of this change may have been more on demand for masters degrees than 485 visas.

The publicly available 485 visa data does not report at the qualification level but, given the timing of the busiest months, at least the bachelor degree graduates with two-year visas would have hit their visa expiry dates in the later months of 2024, which may explain the dip showing in that visa category's time series during that period. The three-year masters grants from that time will presumably have significant expiries in the later months of 2025.

In 2023-24 the total numbers of visa grants are down on 2022-23, but the new visa holders are not going to have to exit Australia so quickly. As well as maintaining the three year masters 485 visa, for students with degrees in areas of skills priorities the Albanese government decided to add two years to the visa time. Bachelor degree graduates with these degrees would get a four year visa and masters graduates five years.

For 2024-25, temporary graduate visa policy changed again. The longer visas for skills shortage fields were abolished after one year of operation. The masters degree time length was cut back from three years to two years, except for Indian students protected by an India-Australia free trade agreement. The minimum English language requirement was increased from an IELTS 6 to 6.5. And the maximum age for getting a 485 visa was reduced from 50 years to 35 years, except for students with research degrees.

Despite all these changes, on a July to February basis, to align with the most recent 2025 data, 2024-25 is runnning about 10,000 temporary graduate visa grants ahead of 2023-24 to the same point. As the chart above shows, by Feburary 2025 the 2024-25 vocational stream grants had already exceeded the full 2023-24 level.

485 visa applications lodged

While 2024-25 temporary graduate visa grants are running ahead of 2023-24 in the same months the reverse is true for visa applications, with 2024-25 running about 30,000 applications behind.

Former students must apply for a 485 visa within six months of completing their course, which puts some constraints on gaming the system. But as the cuts to 485 visa benefits were announced in December 2023, but did not apply to graduates who submitted their applications before 1 July 2024, there was an opportunity and an incentive to get applications into financial year 2023-24.

We can see the consequences in the chart below. For students finishing in first semester 2024 we see that monthly applications for June 2024 (orange bar) were double the equivalent month in 2023 (blue bar). By contrast in July 2024, after the rules change, applications were less than half the equivalent month in 2023.

These timing issues deflated 2024-25 applications and inflated 2024-25 visa grants.

In the second half of 2024 (orange bars), applications continued to be well below 2023 (blue bars) levels with a more attractive visa offer. For January and February 2025 (green bars), which will be people who finished their degrees in late 2024, applications are above 2023 levels (before the visa incentives starting 1 July 2023) but below 2024 levels (while the visa application incentives were in place).

The pipeline of completing students

Regardless of incentives, 485 visa appplicants must have completed a relevant qualification in the last six months. The dip in commencing enrolments during 2020 and 2021 led to reduced completions in subsequent years as seen in the chart below.*

As I said in my Conversation article on the Coalition's policy announcement, the subdued recent numbers of 485 applications could be the calm before the storm. The large number of commencing students in 2023 only started to become eligible to apply for a temporary graduate visa in late 2024, after completing the required minimum two academic years in Australia. Visa grant data suggests that second semester starts are significant, so another significant group will become eligible to apply in mid-2025.

In 2024 the vocational commencing numbers fell significantly and higher education commencing numbers slightly, which will bring down the potential applicant pool at the two academic year mark (i.e. from the end of 2025) compared to 2023 commencers. For higher education, however, the 2024 commencing numbers will still be higher than they were pre-COVID.

Potential post-higher education 485 visa applicant pool will be high by historical standards in at least 2025 and 2026, as 2023 and 2024 commencements complete their courses. As noted above, however, Labor introduced changes to reduce eligibilty starting 1 July 2024. Based on 2023 student age statistics (unfortunately all international students, not just onshore students), 8.8% of postgraduate coursework and bachelor-degree students were aged 30-39 years - so already above the 35 years age limit or at risk of being so by the time they finish their course. A further 1.5% are aged 40-49 years - people who would have been eligible with the previous maximum age of 50 years but clearly not now.

Due to a lack of data, I cannot estimate what difference a minimum English language level of IELTS 6.5 compared to 6 would make. Most universities require an IELTS 6.5 to begin with, so this may not be a major constraint for higher education graduates.

Flows out of 485 visas to other visas

Statistics on the flow of former 485 visa holders to other visa statuses miss a key number, how many leave Australia. The chart below shows those who remain in Australia. We see that moves to other temporary visas spiked significantly in 2022-23. This was mainly driven by the Morrison government's subclass 408 COVID temporary activity visa, which closed to new applicants on 1 February 2024. Other than the 408 visa, the largest temporary graduate visa category for ex-485s was student visas. However this had dwindled to 1,573 in 2023-24.

From 1 July 2024, 485 visa holders could no longer apply onshore for a student visa. I'm still waiting on the release of data for the second half of 2024, but I expect the number of ex-485 visa holders going onto other temporary visas will be small. The main remaining category is the 482 temporary skill shortage visa, with 2,494 granted in 2023-24.

The number of ex-485 visa holders getting permanent residence, however, trended up in 2022-23 and remained at a stable level in 2023-24. This probably mainly reflects the preceding big increase in 485 visa holders (first chart of the post). The 2024-25 permanent migration planning levels show a big cut in subclass 189 skilled independent visas, the second most common form of PR for former 485s visa holders (after the subclass 190 skilled nominated visa). So it seems quite possible that fewer ex-485s will get PR in 2024-25 than in the two preceding years.

If it wins the 3 May election the Coalition says it will grant permament residence to 140,000 people, 45,000 less than the 2024-25 planning level. Obviously that would be bad for all would-be permament residents. Labor has not announced a 2025-26 planning level for permanent migration.

The relationship between perceived prospects of getting permanent residence after a 485 visa and demand for 485 visas is not known. If former international students think that their chances of permanent residence are low they may cut their losses and go home. On the other hand, two years working in Australia may still earn them more money than employment in their home country.

Conclusion

If the Coalition is serious about reducing net overseas migration to 100,000 below Labor it cannot avoid paying attention to the 485 visa.

Expiring 485 visas from the 2022-23 spike in visa grants, 2024 completions that would still have been below pre-COVID levels, and graduates caught by the age or IELTS changes, may cumulatively work against a near-term sharp spike in 485 visa holders above the late 2024 peak.

Over the medium term, however, significant increases are possible. The pipeline of 2023 and 2024 commencing students completing their courses will create larger cohorts of graduates eligible for a 485 visa. The longer 485 visas as a result of policies in place in 2023-24 will slow down offsetting departures. These two factors interacting could produce substantial net additions to 485 visa holder totals.

A lesson I would draw from the last five years of migration policy is that it is better to maintain steady policies, with mostly incremental changes, than to react strongly to the issue of the day - skills shortages and rebooting international education in 2021 and 2022 and bringing down NOM from late 2023 to 2025.

Just as the excessive liberalisation of policy in 2021 and 2022 exacerbated the subsequent NOM problem, the more recent tightening of policy has already crashed international vocational education, risks crashing higher education, and in time could cause new workforce shortages in industries that rely on the labour of international students.

These policy swings are also unfair for international students. They respond to the incentives created by Australian governments, only for the rules to change when it comes time for the Australian government to uphold its side of the bargain. The goal should be stable policy, with grandfathering for existing students when major changes are required.

*Note that we lack an accurate count of relevant completions - the Department of Education's statistical collection does not include some colleges that specialise in international education, and onshore completions with the required two years studying onshore are not reported; I have included all VET international completions when only those in certain fields are eligible for a 485 visa and they too must satisfy the two years of study requirement; some indviduals are counted more than once in the student statistics but can only have one 485 visa.