Demand driven funding for Indigenous medical students - is it a good idea?

In line with a 2025-26 Budget commitment, the government has introduced legislation for demand driven funding of Indigenous medical students from 2026.

While well-intentioned, this policy is unlikely to make any significant difference to Indigenous medical student numbers and could accidentally reduce the number of non-Indigenous medical students.

Is there a problem that demand driven funding can solve?

In his second reading speech, the minister noted the current low number of Indigenous doctors and the benefits for Indigenous patients of Indigenous health care workers.

As with the earlier demand driven system for Indigenous bachelor degree students, however, it’s not clear that a shortfall in Indigenous doctor numbers is a problem that demand driven funding will solve.

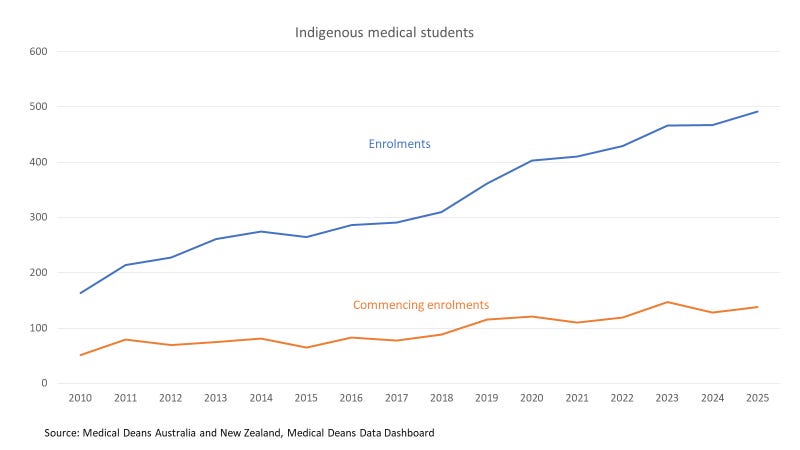

Universities already try hard to recruit Indigenous medical students, with special entry schemes and quotas in some cases. On the available data (below) they are having some success, a source of pride for the medical deans association. 3% of domestic medical students are Indigenous, compared to 2.3% of the overall domestic student population.

The main obstacle to further enrolment increases is unlikely to be funding rather than the difficulties in finding potential students who meet the entry requirements and are not being set up to fail.

The low estimated cost of this policy, $560,000 for 2026-27, or about 17 medical EFTSL, suggests that the government itself does not expect any major increase in student numbers.

A major change in medical student policy

While the expected student numbers are low, conceptually Indigenous medical demand driven funding is a major change - a more radical departure from existing policy than the earlier extension of demand driven funding to Indigenous non-medical bachelor degree students. Demand driven funding for non-medical courses means that all Indigenous bachelor degree students earn Commonwealth and student contribution funding for their university. For non-Indigenous students there is a ‘soft cap’ of maximum Commonwealth contribution revenue (called the maximum basic grant amount). But universities can and do enrol additional non-Indigenous bachelor degree students on a student contribution only basis.

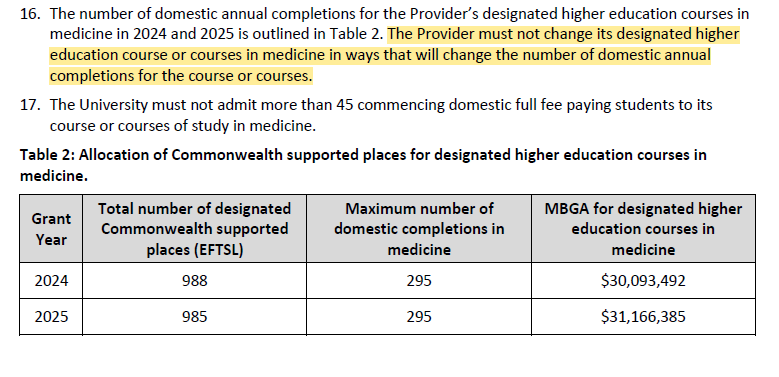

By contrast medicine is hard capped. It is a ‘designated’ course, which means that it has a specific number of student places allocated. While designation of itself does not prohibit over-enrolments, for medicine added clauses in university funding agreements (section 16 in the extract below; U of M but other unis have equivalent provisions) tie universities to specified numbers of domestic medical degree completions. Over-enrolment in ways that would alter completion numbers would result in a funding agreement breach.

Demand driven and designated funding are the polar opposite policy approaches in the student funding system.

Implications for the medical student capping system

Controls on medical student numbers are a long-standing part of the higher education system. I haven’t found a detailed history, but at least by the 1980s there was pressure to reduce medical student numbers from the AMA (claiming concerns about underworked doctors not maintaining skills, but presumably mainly worried about competition) and the Department of Health, worried that more doctors would lead to ‘overservicing’ with consequent costs to Medicare.

Introducing demand driven funding for Indigenous medical students will not in itself make any difference to the completions cap, which operates independently of designation.

If the cap remains unchanged, to the extent that the policy makes any difference to Indigenous medical student numbers there will be a corresponding reduction in non-Indigenous medical student numbers.

Given the low likely numbers, I expect any additional Indigenous medical students will be put into a model of future completions and the cap adjusted up.

The transition between funding systems

As with the previous Indigenous demand driven system, the first step in moving to the new system will be, at each university with CSP medical courses, a reduction in designated places equivalent to existing Indigenous students. The minor expected funding increase is consistent with this approach.

If a university has designated medical places transferred to estimated Indigenous demand driven places, and then ends up with fewer commencing Indigenous medical students than anticipated, its total number of medical students will decline. The volatility in commencing Indigenous medical student numbers visible in the chart above shows that this is possible.

As I keep saying about the government’s policies on student places, the more conditions they add to a place the lower the chance of finding a student who can tick all the boxes. With broad student eligibility criteria unused capacity is less likely, especially in medicine where there is significant unmet demand. With narrow eligibility, such as students with a specified personal characteristic, the chance of unused places increases.

Conclusion

Indigenous demand driven funding for medicine will probably make no difference to the number of Indigenous medical students, which is already being maximised, while risking fewer medical students overall if Indigenous commencing numbers unexpectedly fall short.

As with the planned limits on over-enrolments, I don’t think the practical consequences of this policy have been sufficiently thought through.