Are the government's policies working to reduce international student numbers? Part 1, student demand

From late 2023 to July 2024 the federal government implemented at least nine policies to reduce international student numbers. With full 2024 student visa data released late last week this is a good time to assess how well (or how badly, depending on your point of view) these policies are going.

This post looks at the demand side, how many student visa applications have been lodged. A subsequent post will look at the supply side, visas granted.

The main findings are that the government's policies have worked to substantially reduce demand for vocational education overall and from migration-sensitive countries in higher education, such as India and Pakistan. However 2024 Chinese higher education applications were down only slightly on 2023 and remain up on 2019. The impact on other traditional higher education source countries such as Malaysia, Singapore and Hong Kong was also muted (all slightly up or down).

Overall demand

As can be seen in the chart below, in 2024 the Department of Home Affairs received 429,691 student visa applications. This was down 20% on 2023, but still above 2019, the last full year before COVID migration restrictions distorted supply and demand.

I thought that 2024 might have been a more 'normal' year anyway, without COVID pent-up demand inflating applications as it had in 2022 and 2023. January 2024 demand was slightly higher than in January 2023. The other 11 months of 2024, however, all recorded fewer applications than the corresponding month in 2023.

Encouragingly for the government, from July 2024, when its full set of demand-deterrent student visa policies were in place, 2024 monthly total applications were also below 2019 figures in four of the six months. Taking just the six months from July to December 2024, demand was down 27% compared to 2023 and 9% compared to 2019.

Vocational education

Vocational education has always been more migration sensitive than higher education. We can see in the chart below that 2024 total applications were below both 2019 (down 6%) and 2023 (down 25%). But in March and June 2024 vocational applications exceeded the already high March and June 2023 figures. The likely reason is policy start dates (other than the increased visa fee) announced prior to policy commencement, with applications received prior to these dates assessed using the old rules. Would-be students rushed to apply before the rules changed.

This bringing foward of applications would have reduced numbers for subsequent months. Even so, the drop in demand for the six months July to December 2024 is very large - 36% less than in 2019 and 45% less than in 2023. The 4,306 vocational applications received in December 2024 is the lowest for that month since 2013, including the COVID years.

The vocational education 'indicative cap' for 2025 was a little over 94,000, but based on average monthly demand since July 2024 that would exceed the number of visa applications by more than 20,000. [Note: These caps are not binding under current rules.]

The government has successfully suppressed vocational international education with migration policy alone. Enrolment caps may further reduce student numbers at vocational education providers that have not already lost their international market, but vocational caps now seem unnecessary at the sector level.

Higher education

International student demand for higher education was more resilient than for vocational education. Compared to 2023, 2024 applications were down in every month except January. But compared to 2019 demand remains strong. Even after all demand deterrents were in place by 1 July 2024, and some universities stopped accepting students in anticipation of enrolment caps, applications were still above 2019 levels from September to December.

These figures may confirm a view in the government that student visa deterrents are not enough in the higher education market. The may also support a conclusion that some universities and other higher education providers will not voluntarily constrain themselves in the international market (prospective students can only apply for a visa once they have a confirmed enrolment). It will be interesting to see how many of these providers keep 2025 commencing enrolments to around their indicative cap.

The indicative caps for higher education provider commencing students total around 176,000. While this is well below 2024 visa applications, there are exempt categories such as students from the Pacific and Timor Leste (5,337 applicants in 2023-34), students on government scholarships, and students in some twinning programs. On the other hand, in the case of packaged courses one visa could lead to commencements in two providers, which would be counted twice under the capping rules.

Onshore applications

Some migration rule changes apply exclusively to onshore applicants (bans on applications from onshore visitor visa or temporary graduate visa holders) or are more likely to affect onshore applicants (showing how a second student visa would build logically on previous courses taken).

Onshore applications in 2024 exceeded those in 2023 - partly because of the COVID dip in commencements leading to fewer completions in 2023 and so fewer people looking to take a second course - but also 2019 numbers. For 2024, we see spikes in March and especially June as applications were lodged ahead of rule changes.

On a six month analysis from July to December 2024, however, we can see the likely start of policy effects - applications down 7% compared to 2023 and 22% compared to 2019.

Age

Student visas have no formal age limit but the government did impose an age limit of 35 years for temporary graduate visas (with exceptions, most importantly for graduates with research degrees). This started on 1 July 2024, so the chart below shows only the last 6 months of each year for comparison purposes.

The age limit on a subsequent visa seems to have deterred some prospective students. Numbers in the 35-49 years age group went down but were never large. The big apparent effect is for people aged 30-34 years at the time of their visa application, who are likely to complete their courses at age 35 years or higher. The decline in visa applications in the 30-34 years age group is 71% compared to 2023 and 51% compared to 2019.

Other changes to the temporary graduate visa, including making it shorter, are harder to analyse. But the significant change in demand seen with the age restriction suggests that these may also flow through into reduced student visa applications.

Source country

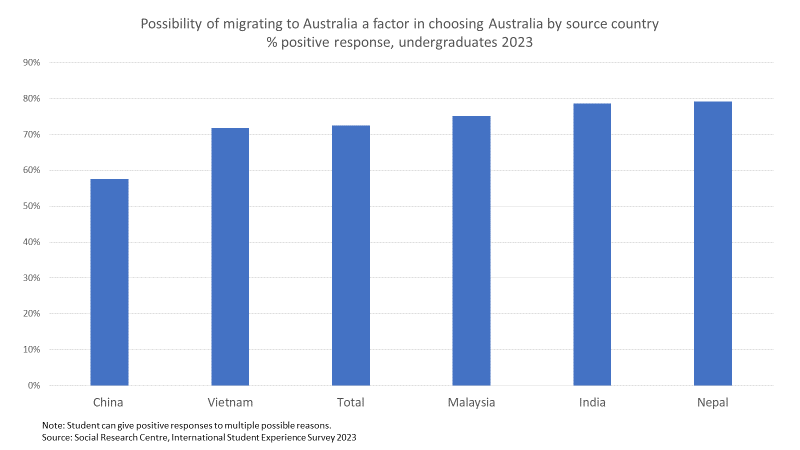

The Student Experience Survey asks international students about the importance of migration in choosing Australia. Unfortunately data is only released for a small number of countries, but the 2023 data confirms that students from India and Nepal are the most migration motivated, while students from China are less concerned about this outcome.

The higher education data below, using the last six months in 2024 after all the new student visa rules were in place, is broadly consistent with the migraton survey. Compared to the last six months of 2023, Indian applications fell by 37% or more than 11,000. In percentage terms, applications from Pakistan were twice as affected, down 76%. The Chinese market, by contrast, was down by less than 2% compared to 2023 and was up on 2019 results. Applications from Bangladesh, Indonesia and Malaysia increased.

In vocational education, as expected from the aggregate data, the percentage falls in applications for the last six months of 2024 compared to 2023 were larger than in higher education. Applications from the Philippines, Vietnam and Kenya were down by more than three-quarters. Brazil was an exception with modest growth in 2024 compared to 2023. Several countries - Colombia, Kenya and Fiji - were however up on 2019 figures.

The next post will look at visas granted, incorporating the effects of changes in migration rules and practices on the chances of a student visa applicant achieving success.